fútbol

I couldn’t write this post until I knew the end of the story. And for that, I had to wait all year. But now we finally have some closure to this complex saga. It begins something like:

Once upon a time, an American family moved to a little neighborhood in a little city in Spain. They were eager to make friends and jump into life in a new country. When they heard about the local children’s fútbol team, made up of students from their kids’ new school, they were thrilled that their son wanted to join. This was great news. The parents hoped it would ease his transition and help him make friends.

Then they discovered that practice would be twice a week, for an hour and a half with games or tournaments every weekend, for… nine months. Visions of their time in Spain becoming an endless parade of fútbol related activities flashed before them.

“Are you sure you want to join the team?” they asked, trying to remain neutral.

“Yes.”

Alright then. Practice began. The boy was happy. A month later they discovered that the reasonable 15 euro a month fee they’d heard about was actually in addition to the 150 euro fee to join and the 90 euro fee for the uniform kit.

“Are you sure you want to stay on the team?” they asked their son, failing at neutrality. “If we pay all of this, you can’t walk away.”

But no. He was having fun running, kicking, making friends. “Yes, I want to stay. I won’t quit. I promise.”

Alright then. A month later the pre-games started. But the boy wasn’t allowed to play. “He’s not good enough,” said the coaches. This candor surprised the parents, who were used to (and sometimes annoyed by) the American-style everyone-plays-everyone-wins approach to kid sports. Happily, the boy agreed with the coaches. He realized that the level of skill and seriousness for the game in Spain, even for 3rd graders, far surpassed the two-month YMCA volunteer-coach leagues he’d previously experienced. He knew he had a lot to learn. The parents, impressed at his patience, were still enjoying their free weekends.

Then the paperwork came in. A mountain of paperwork. A mountain of paperwork the parents had to translate, notarize, attach documents to, visit government offices about, fill in, pay for, and sign. Proof of visas, proof of residency, proof of income, lease bills, letters from employers. Insanity. “It’s because of FIFA,” the coaches said, in incredibly thick Andalusian accents. “The foreign kids can’t play without the paperwork.” Sure enough, the real games had started and the boy, along with his expat friends, weren’t allowed to play. Why? Well, the answer was slow to emerge (with the family’s limited Spanish), but they finally uncovered the big story. The previous year, a youth team in Barcelona recruited incredibly talented foreign kids to play in their clubs, offering large sums of money in the form of moving the children’s families to Spain, including liberal living expenses. While no one was shocked to discover more corruption within FIFA, everyone was dismayed that the stricter rules now applied to non-super-star-children who just wanted to play on their neighborhood team.

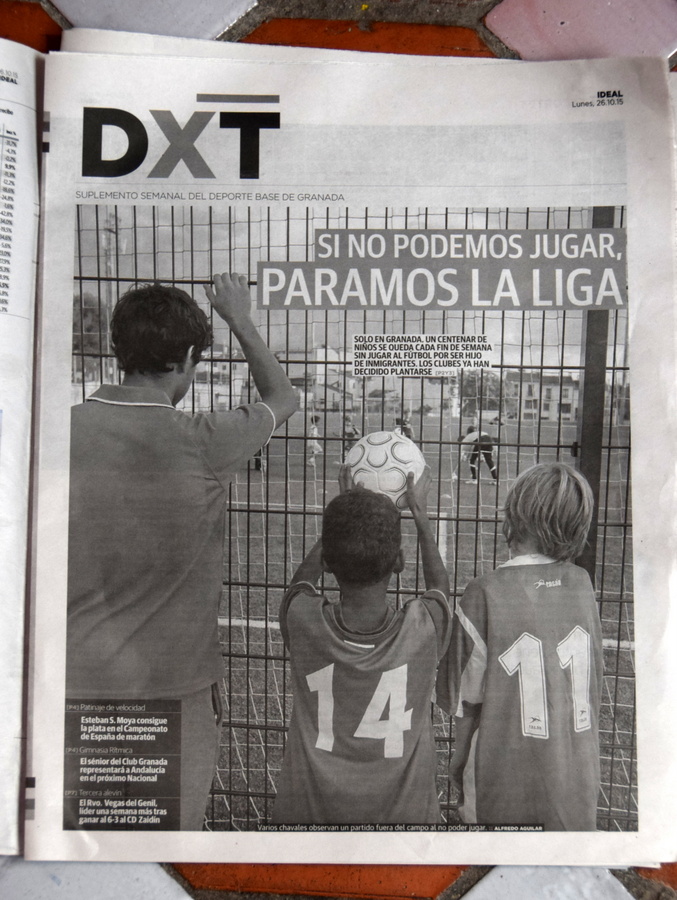

The local newspaper picked up the story and asked the expat children to come for a photo shoot. “Look sad,” the photographer directed, snapping pitiful pictures of them outside the field, looking wistfully at a game being played by their peers.

And yet, the really talented foreign kids did get to play. This was accomplished by a little slight-of-hand on the part of the coaches, but the implications were not lost on the boy. He knew that even if FIFA said his paperwork was complete (which they never did), his coaches would not let him play. At that point, however, he seemed resigned to his fate. The parents kept waiting for the other cleat to drop.

And then it did. He started to become frustrated with practice. He got teased by his Spanish teammates and cursed at when he made mistakes, which was often. The coaches split the team into two groups: the good players and the bad players. The “bad players” ran endless drills or sat on the sidelines while the good players practiced in actual scrimmages. No sugar coating. This is Spain. This is fútbol. The parents saw all of it, but didn’t know how or if to protect their kid from this cultural norm. The boy often left practice frustrated and tearful.

The parents, on those long walks home with the boy, talked of grit, and the joy of learning new skills for the sake of learning new skills, and the fact that even the lousiest player on a Spanish team will dominate the YMCA league. He didn’t want to continue, but he didn’t want to quit. Soon the parents started sneaking him squares of chocolate on the way practice. (After all, it worked for Harry Potter against the Dementors) They promised him a day off once a month. They encouraged his determination and tried to give him strategies to deal with tough coaches and bullies. (“Pretend the ball is his face.” or “Shoulder shoves are totally legal in fùtbol. Let’s practice hitting those kids as hard as you can.” or “Of course you’re angry. Use it.”)

Maybe all of this helped. By spring, the parents figured he had been through enough. He had practiced through heat, rain, freezing temperatures, bullying, and boredom, and he still couldn’t bring himself to quit. His parents told him he had certainly paid his dues and they were fine if he did. But no.

The coaches managed to join a tournament that, for some mysterious reason (probably because the season was technically over), allowed the foreign kids to play. So one hot Saturday morning, the families all carpooled to a nearby suburb and waited anxiously in the stands for what could be (if their team continued to win) an all day activity.

Of course they lost the first three games and were eliminated. But! The boy got to play. In a real game. In Spain. For about 15 minutes.

It was a triumph… of sorts.

***

So, was it worth it? Well, I can’t say that my heart didn’t break for him many times this year. He never won over his detractors, or scored a goal in a game. But he improved so much and, more importantly, proved to himself he could power through a tough situation. He knows that whenever he faces something difficult in the future, he can draw on this experience… Or chocolate.

That made me cry. What a strong, determined, and resilient boy. I want to hug him.

Thank you for this new understanding of the nuances and challenges of Boy-o’s soccer experience. I knew is wasn’t going well, but I understand so much more now! You are all winners in my book!

Oma

I did cry. At work.

Too upset to comment! #&%*(#@!!((*+&*!

Rob and Cheris,

For the past three days, Dad and I have both been too emotional about this to even offer a comment. It pains us to think about your and G’s frustrating soccer experience . I have so many things to ask you about it ; it would be great if one of you could call us to have a brief ( I promise!) conversation about it when you have the chance. For now, I just want to say that you and your sweet brave boy were amazing in the way you handled it every step along the way.

An amazing story! Kudos to the boy and to the parents.